homepage & table of contents >> appendix 2

Blackaeonium Archive System Specification Document (and additional technical information)

Blackaeonium Archival System Specification Document (updated 2007, 2010, 2011)

Context – What & Why?

Based upon a needs analysis, the archival system was designed to work as both keeping place and workspace for creative content. The decision was made to create a relational database-driven website to allow a central location to store digital objects and documentation of digital/analogue content.

Basis:

- Metadata standards – Dublin Core & ISAD(G) & curatorial tools like the VMQ

- Why

Dublin Core?

Common, minimal, easy to develop interoperable outputs such as RSS & RDF. - Why ISAD(G)?

International standard – minimal requirements for archival description. Addresses multilevel description. - Why

VMQ?

the Variable Media Questionnaire is specifically addressing the needs and intent of artists and their works. Although more of a curatorial tool, than an artists tool, elements of the questionnaire are valid for the artist to consider at the point of creation of artworks, and elements of this should be captured in the artist’s archival system – especially information about source, materials, environment, installation and artistic intent.

Scope of the system: what it will and won’t do

The system will not fully replicate the types of archival systems used by large institutions simply because these systems are too complex and data entry for this project needs to be fairly quick and easy to do. The system will document the essential metadata deemed necessary for documenting artworks of individuals or small groups without institutional intervention or before/beyond institutional selection. The system will focus on creativity and decision-making, and recombination of archival objects to facilitate the development of new artistic work, so grouping content will be an important part of the system and interface design. The idea of a “recombinant poetics” (Bill Seaman) is an important functional requirement of the system as it is hoped that the system itself at every level will be a part of the artwork.

The structure of the system has been left fairly open because it is not known what types of information will need to be documented. There are three open descriptive fields to allow for text description of the content of the work, the technology used, and “other” to accommodate other possible elements that need description. These fields should allow for the type of documentation prescribed by the variable media initiative in describing the source and materials of an artwork, how it is presented to an audience, and the artist’s intent for future preservation and presentations of the work – curatorial as well as archival:

We need artists—their information, their support, and above all their creativity— to outwit oblivion and obsolescence. That is why the variable media approach asks creators to play the central role in deciding how their work should evolve over time, with archivists and technicians offering choices rather than prescribing them. (Ippolito 2003)

Evaluation

the artworks & the artists & the audience test the system. If something doesn't work, it gets noted in the research blog, and changes are made. The ultimate evaluation is through exhibition and presentation of artworks – and physical and online exhibition of elements of the archival recombinant works and new works derived from the archive.

Ultimately, the long-term preservation of content in the archival system will need to be evaluated, but it is difficult to ascertain when preservation strategies will need to occur. Strategies are already occuring with regard to media types that are rapidly changing such as Flash animation and other third party applications such as games software. The strategy that best suits the needs of this project and will hopefully fulfil future requirements, is the reinterpretation of content in other formats - the creation of metacontent documentation of variable media in other formats such as image, video, text description, etc.

Database Structure

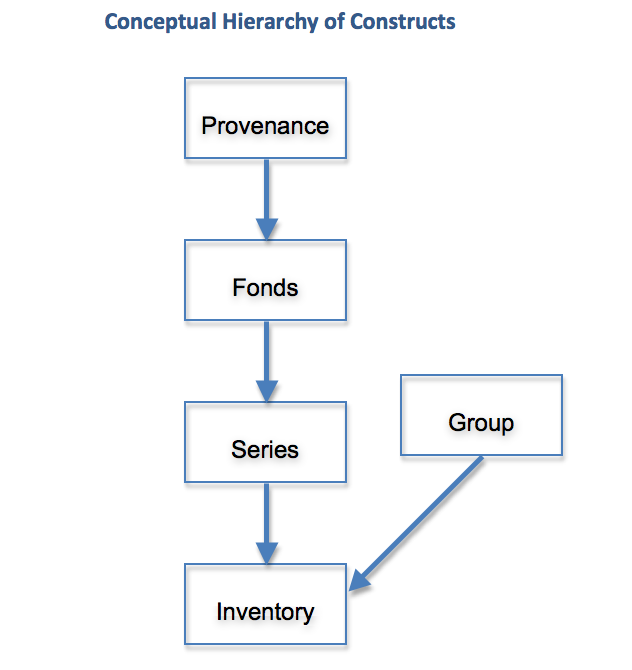

Conceptual structure or "Domain Model"

Provenance Entities create Fonds (Collections/Assemblages) which contain Series of Inventory Objects.

Groups are created by remixing Inventory objects across the archival assemblage at any point in time.

The system contains multilevel description (ISAD(G)) from fonds/collection, to series, to inventory (items). Groups are a part of the descriptive levels, which may work in a similar way to sub-series, but they are not archival constructs like series, they are creative constructs that allow for the recombination of content and the creation of new works through remix and experimentation with juxtaposition of items – in effect, allowing for the explicit documentation of a process that artists tacitly engage in.

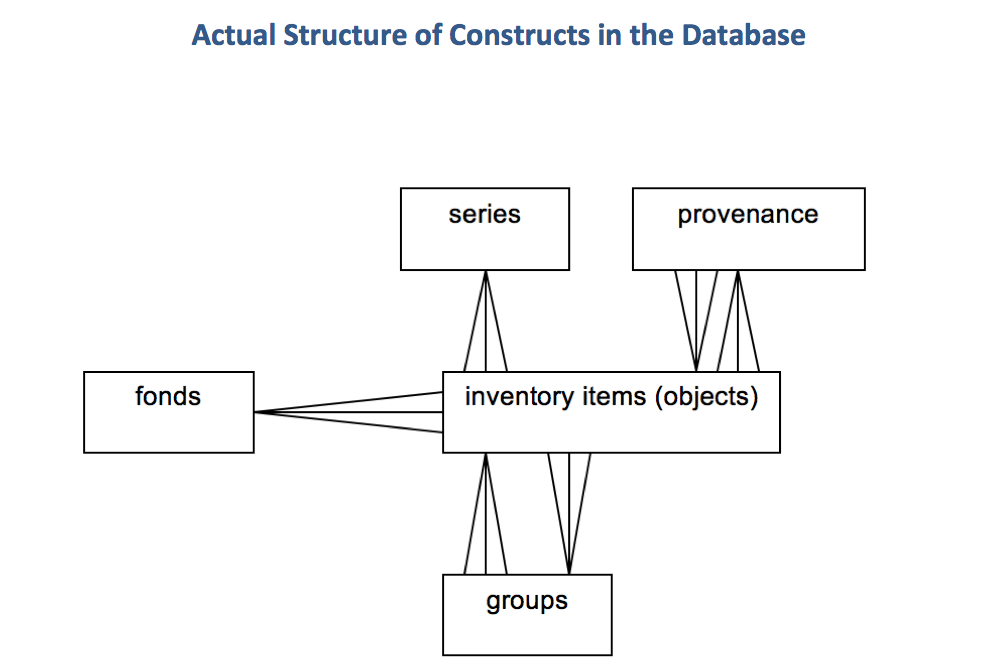

The system structure uses many Dublin Core elements at the Inventory item (object) level, but incorporates many of the ISAD(G) elements required for multilevel archival description (see the table of field definitions to see where fields meet DC and ISAD(G) standards).

The Inventory item (object) is the central point linking to Collection (fonds), Series, Provenance, Groups, Relationships, etc. Secondary levels of interconnectivity – relationships between Series, Provenances and Groups Most relationships happen through the Inventory item, but there are some relationships defined between contextual elements.

The system is not a flat, single entity system, nor is it the full 5-level entity record keeping system prescribed by the National Archives of Australia – this would have been too cumbersome to both build and implement within the limits of this research, and in fact, many smaller systems for documenting heritage collections such as Omeka and CollectiveAccess, do not follow the complex structure of these institutional archival or record keeping systems. We need to spend minimal time on documentation for maximum output, and that is the justification for this system’s design.

Rather, in the spirit of the recombinant work that is being created through this research project, the system itself is a remix of elements drawn from Dublin Core, ISAD(G), the Variable Media Initiative Questionnaire elements, blogging tools, and technical elements common to many websites such as jQuery, RSS feeds, RDF outputs etc. The layers of recombination and remix permeate the whole framework for the archival assemblage, and work in tandem with the idea of a creative archival continuum from the process, to the content and the framework.

The system allows for the description of provenance “entities” such as artists, organisations, etc (both ambient entities and creating entities) and allows for the linking of these entities via provenance relationships. Thus far it hasn't been necessary to describe complex ambient entities, the only ambient entity exists in the ACW archive. ACW is defined as the ambient entity and Lowe and Riva are the record creating entities that are a part of the collaborative duo known as ACW. The Dublin core field for “contributor” allows for the distinction to be made between the “creator” provenance, and any participants in the artworks. There is scope to extend the system to allow for more complex relationship building between provenance entities, and series entities also, but no specific fields that would satisfy all the requirements for a system as prescribed by an institutional archive like the NAA such as “mandate” or “business”. This wasn't required for the research as the target artists were individual or very small collaborative groups that don’t have the same requirements of government agencies for documenting change – although it would be possible to describe some elements like “mandate” in the description fields at various levels, or to create an additional section for mandate that could be easily linked to the inventory with a joining table.

It was also decided not to include a level of description for archival “accession” because the system is designed for artist users that are both creators and custodians of their own content. Upload and capture by the system is recorded automatically. There is no official “ingest” policy or process as items may be added in an ad hoc fashion as they are created, or as they are deemed to have archival value.

The system details contain a description field that may be used to describe the purpose of the archival system, and this may possibly be used to reflect if custody of the whole collection/assemblage has been transferred from the artists’ custody to some other stakeholder. This may be an area for future development.

Disadvantages of the full five entity recordkeeping system include:

- its implementation is more complex than a single-entity, two-entity, three-entity or four-entity system

- it requires the use of a defined relationship syntax

- it has greater difficulty in maintaining metadata over system boundaries and over time.“

Australian Government Record Keeping Metadata Standard Implementation Guidelines, National Archives of Australia, version 2.0, June 2011

It is hoped that the Blackaeonium system in it’s simplicity, which is at best closest to a 2 or 3 entity system, (record, agent, relationship) will be easier to implement, is open to much more rapid development where necessary, and will be more interoperable through the use of standards like Dublin Core Metadata for the inventory structure.

The limitations of Blackaeonium system are that it is not object-oriented in design and thus, may be limited in expressing complex relationships between entities such as records, agents, and relationships, but so far, it has been able to document the types of entities in all of the case studies – single or small collaborations of artists – exactly what it was designed for. There is no duplication of information, which is one of the disadvantages listed by the AGRKMS guidelines because it tries to conform to the ISAD(G) multilevel archival description recommendations.

The Blackaeonium system allows for the description of what Chris Hurley calls “contents entities” (Hurley 1994) in keeping with the Australian Series system. It was not known initially what granularity of description would be needed at the series level, but it seemed occur naturally with either content developed for a single artwork or a series of artworks; and with groups of items created for a particular purpose or function, using a specific medium. The Inventory level description also can have multiple granularities from a single file to a group of files that make up a website for example. In most cases, the inventory item is a single file that can be uploaded and presented as an embedded media file or as a link to download if it is not of a format compatible with presentation on a web browser.

Because a crucial requirement of the system design was to allow for presentation and experimentation with the content in the system, it was necessary to consider that the types of content to be documented and added to the system have a dual purpose – as a digital copy of some kind of creative content to be documented and preserved in context, and also as a piece of content to be viewed, manipulated, and recombined with other content to create new work.

(See Table Relationships Diagram in Appendix 4)

Table & Field Definitions & Potential Usage

A minimal field set was developed for the system with the idea of keeping the potential usage quite open – it was not known initially which fields would be most useful and how they could or would possibly be used.

A minimal set of fields within a multi-layered structure was created that most closely compares with Dublin Core metadata Standards & ISAD(G) version 2.

(See Appendix 3 for tables and field definitions and descriptions for prototypes 2 & 3).

Access

Different levels of access are required to enable administration of the content in the system, and to ensure security, reliability and veracity of the content. The levels of access are:

- Public User – no login required – can search and view “open” items

- Guest User – login, no data entry except for tagging and user groups “Guest Remixes” – can search and view open and closed items

- Admin User – all levels of access

Outputs

Types of web interfaces and outputs possible with the Blackaeonium system:

- Standard Web page outputs – lists, accordion style collapsing summaries, draggable layers (using HTML, CSS and JavaScript with underlying PHP code to serve content from the MySQL database)

- getID3() text based output (reads the ID3 metadata within content objects)

- XML

outputs – can be repurposed for Dublin Core, RSS or other EAD outputs & outputs as METS or MODS although these have not been created

yet as there has been no requirement for this type of output. It is

hoped that a way of accessing the VMQ “Metaserver” might be possible.

- RSS output (XML for syndicated feeds)

- RDF output (for semantic searching) – under development

- PDF

output (for selected printed hard-copy output) – under development

(see PhD Research Blog for specific developments)

Additional concepts & wish-list for future developments

- Additional semantic web access – RDF, RDFa, Microdata, Microformats, FOAF, Schema.org etc – links to the VMI “Metaserver”

- 3D interfaces using Unity, Flash or Second Life

- additional HTML5/CSS3/ jQuery interfaces as required for specific case studies

- additional developments to the Wordpress interface to generate RDF for specified groups, items, series, fonds or documents

Other archival systems investigated

http://OMEKA.org

http://archiviststoolkit.org/

http://www.archon.org/

http://www.collectiveaccess.org/

http://www.ica-atom.org/

Additional Information Relating to Technical Developments

System development

The first task involved design of the relational database structure. The design process for the database structure initially used some basic structures taken from observations made about other archival software systems during the theoretical and technical research, and my own previous knowledge of similar systems. Over time, this structure was then redeveloped and extended to include additional elements to enable system functionality beyond the basic structures, to allow for more complex mappings and interrelationships between objects in the system.

The second task involved the coding of server-side scripting files (PHP in combination with other scripting languages) to create the web-based interfaces to the database and objects linked to the database, and to provide for the functionality of the system. The PHP files were coded specifically to enable certain system functionality, and then tested for suitability, redeveloped, and retested repeatedly to keep refining the functionality. Evaluation continued in the development phase, as the research proceeded, to see if developments were in line with proposed outcomes, then making changes where necessary to make those outcomes actual.

Once the first prototype was constructed, data was inserted into the system to test whether the various functions were working successfully, then areas were noted that required improvement or redevelopment. The process followed a cyclical routine of development, testing, bug fixing, evaluating outcomes and improving on development. The system went through several versions of construction, with three main prototype versions developed over the course of the research . The first prototype is no longer functional, its parts are archived in the PhD Blog. The ACW archive is an example of prototype 2, the Blackaeonium archive and the At Home series archive are evidence of prototype 3, and Atemporal is currently in development as prototype 4.

System development is still ongoing – There is no final outcome or solution. A software system must be continually reappraised. New system developments will continue over time to meet the needs of users. The system developed for the Blackaeonium archive has been developed as a prototype - to a certain level of functionality to meet all the requirements of the research project thus far, but the intention is to keep developing it beyond the scope of this research project to add further functionality, improve usability and to add other ways of presenting the content and metacontent to generate further recombinant works.

The Ambient Framework – Database/Internet

The database in the Blackaeonium archival system allows for the mapping of personal topographies – one can revisit a location, or take new paths by connecting points never connected before. These processes are leading to the generation of new works and recombinant works from the system. The recombinant works can be viewed as individual works in themselves, or may be used as points of departure or developmental works for new works created outside of the system.

For example, “Narcisse Revisited” and “Bubble Girl with her Damaged Sisters #2” are recombinant works derived from objects within the Blackaeonium archival system. These objects were used in other projects in a completely different way, but through navigating the Blackaeonium archival system, searching for specific objects, and then recombining them through a particular visualisation, successful, new artworks were formed: partly by chance (with “Narcisse Revisited”, random placement of objects and accidental incompatibilities of the file formats and a browser glitch make the Flash content objects flicker on the screen); and partly via a decisive trajectory through the content to accumulate these particular subsets of objects as new Groups or “works”.

Questions about the long-term nature of these open/becoming artworks are raised – will the archival assemblage ever be complete? Will I ever decide to stop adding to my own archival assemblage, and if so, will that constitute “completion” if the audience continues to engage with the work and remix content? If the database is still recording interactions can the work truly be finished?

Discipline and friendly tools: how much documentation?

Through this research, the need was identified to use systems to assist the development of quality documentation, but a system does not do the work by itself. The old database development adage, GIGO (Garbage In Garbage Out), is particularly relevant here. This research is proposing that artists need methods, processes, and discipline to create adequate archival documentation. From the vast array of personal sites using Web systems currently on the Internet, it would appear that in general, web users are becoming more practiced, disciplined self-documenters. Many of us are bloggers, video documenters and contributors to a variety of social software web sites (Owyang 2010). If artists could push these self-documentation disciplines further to include archival quality documentation along with the more immediate content currently being documented, it would be extremely worthwhile in the long-term and the short-term for access and preservation.

I have found through my own experience, that an individual with a high level of motivation to undertake archival documentation still requires tools to make the process easier. An artist/archivist who is fairly disciplined about documentation, will still tire after an extended time with any kind of repetitive task – and data entry into an archival system can be a repetitive task. The development and use of tools and templates can save the user from some of the more tedious aspects of data entry.

Past personal experience with the failure of a system to be supported by users (due to the level of work required to enter data) is a cautionary tale that I always keep in mind [1] . As a user, one wants to get more out of a system than one puts in. Users do not want to spend hours documenting if they barely need to use the content or objects they are required to document. There is no immediately perceived reward for the work. The archival documentation may have a worthwhile outcome at some indeterminate point in the future, but at the present time, it may seem like a futile exercise.

The Blackaeonium archival system is endeavouring to avoid this failure: partly because it is a system that is initially being built as a creative tool – there is a desire to use it for a number of creative reasons; and partly because there is an immediate advantage and a long-term advantage in using the system. The user can immediately begin working with the content objects, playing, grouping and recombining the content, and immediately make it available on the Internet. The content has enough quality metacontent to give it longevity for future access.

Amongst other functions and interfaces, an interface was developed that allows the user to choose an existing object to create a new object, then change the relevant data to create new object documentation and upload a new file to the system. This has proven to be very successful as a time saving device, particularly as there often are several objects of a certain type to upload to the system at the same time – a series of still images, for example. With the option to use an existing object’s data as a template for a new object, repetitive typing is minimalised, and it is possible to insert content into the system extremely quickly and relatively easily.

Building traces, flows and narratives

Personal Collection Policy

Archivists can only document context based upon the information available at a given time and place. Collection policy, whether in an institutional archive or a personal archive always exists on shifting ground. It is only over time that the impact of decisions to keep or destroy can be seen. Collecting is an ongoing process to be re-read and reviewed over and over again. The decision to archive is crucial to the overall shape and form of the collection, and to the narratives that we create by keeping and destroying.

Yet memory is notoriously selective -- in individuals, in societies, and, yes, in archives. With memory comes forgetting. With memory comes the inevitable privileging of certain records and records creators, and the marginalizing or silencing of others. […] Postmodern philosophical and historical studies of the archive in recent years only underline its contested nature as mediated sites of power, ideology, and memory. (Cook 2000, p.5)

Sue McKemmish (1996) describes recordkeeping as a means of “keeping the narrative going”, and the record as being “in a constant state of becoming” (McKemmish & Upward 2001, p. 8). The archive is not an inactive repository, but a living, organic collection or assemblage of material. The constant reading and reinterpreting of the collection or parts of the collection may tell us different stories, and could potentially inform us in many ways.

The questions “What do we keep and why?” and “How do we change our collection decisions over time?” are of interest to this research because the selective process in archiving is similar to the creative selective process.

For my archival assemblage, determining what to collect was a part of the process. Some items were selected because they are completed works that have been exhibited. Other works were selected for their potential to be used in future works – they haven’t formed parts of major finished works, but they have an aesthetic value, or relate to a specific idea or concept that has not been fully explored yet, that I may want to examine further at some point in the future. As in the artist’s visual diary, all kinds of content may be collected – observational sketches, notes, concepts, quotes that are resonant, snapshots of “stuff” from every day life – all of these may be used and reused in the archive, and may be a point of departure for creating new work.

Remembering, Repressing and Forgetting

By creating content and preserving it, McKemmish states that we as individuals are creating evidence of me… (McKemmish 1996), whether artist or diarist. What do we choose to save (remember), however, and what do we choose to destroy (forget)? Subjectivity, veracity, secrets and lies are tantalising creative areas to explore in personal archiving. There is tension between the archival requirement for authenticity, and the fictive elements that could be placed in the archive. Not only are our decisions about keeping content subjective, and subject to change, but the truth as we perceive it is also unstable, and we may choose not to reveal the truth, or we may choose to invent or fabricate when creating and documenting. The archival act is a subjective decision in space-time.

Archives are not neutral: some facts count, others are excluded. […] for the registry office in the Netherlands, children who die before being registered, were never born. (Ketelaar 1999)

Just as any collecting archive will have a collection and retention policy that exists on shifting ground, we as individuals repeat those patterns on a micro level – there is flux in personal archiving. Sue McKemmish (1996) uses the author Patrick White as an example of someone who radically changed his personal archival policy. He went from being a destroyer of records – destroying everything including drafts of manuscripts because he thought that only his novels “counted” - to later in life becoming a record keeper and a self-documenter.

Even when acting in good faith, to preserve the veracity of the object being archived, we can only work with the available information, and our interpretations of it at that time. How we think and feel at a particular point affects what we document, and what we interpret as the meaning and significance of an object.

Essentially the recordkeeping intervention has to do with storytelling. Recordkeepers tell stories about stories, they tell stories with stories. And narrativity - as Michael Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Hayden White and others have demonstrated – as much as it might strive to work with actual events, processes, structures and characters, in its form – structurally – brings in certain fictionalisation of what Paul Ricoeur calls these immediate referents. For the form of narrativity – like all forms – is not merely a neutral container. It shapes, even determines, the narrative content in significant ways. (Harris 2001, p16)

The Blackaeonium archival system allows the creator/custodian control over all aspects of the system – to enter false documentation, to destroy content and metacontent, or to include content that is restricted (secrets) and thus excluded from certain potential users or the general public.

One can remember by placing objects in the system and carefully documenting them. One can forget by excluding objects from the system, by documenting false information about how an object was created or what it means - how we understand it. One could repress in a number of ways – by closing objects off from public access, or by not linking objects (by metacontent) to other objects, which would limit accessibility via various trajectories through the database. The possibilities for shaping content in the archive are endless. For the artist, the process of archiving holds many possibilities, not just for accumulating a collection over time, but also for actively creating a multiplicity of artworks and narratives.

Content/Metacontent Development

Once the system attained a certain level of functionality, it was possible to start documenting content objects. The objects initially documented were outcomes from my own creative practice. A large quantity of material exists, saved in a variety of file types including text, still image, video, animation, audio, database and proprietary software files. Many of these objects are born-digital[2] media, but there also exists a backlog of files representing older analogue works that have been documented with digital media. These are mostly still images.

The archival documentation involved entering data about the objects into the archival system, and uploading the objects to an online server space – each object then becoming accessible via a permalink[3] URI (Universal Resource Identifier) stored in the system along with the other data about the object.

Once the content was uploaded and documented, it was possible to begin investigating ways of building the rhizomatic relationships between objects through the database structure, interfaces and documentation.

This was seen as a crucial part of the research – linking objects and creating trajectories through the database was the main way of creating recombinant works from the system. The archival metacontent in the system creates context and meaning for the objects linked to the system. These relationships were built through using the system, constructing the relationships through data and documentation, and then examining ways of presenting this data in a meaningful way to show the object in context and the relationships between objects.

Metacontent as a Concept

If metacontent can be defined as “content about content”, then in the case of the Blackaeonium archival system, metacontent exists as a multiplicity in the archival assemblage - it is in the data, the metadata and the content objects that populate the system. Metacontent permeates the whole environment.

Metacontent is one way of creating relationships between content objects. These relationships enable endless ways of connecting points in the database, creating trajectories for the user to move through. Relationships are formally and informally recognised in the Blackaeonium archival system and are stored as metadata and metacontent within the system. Over time, relationships and links build and increase in the database, establishing patterns and topographies that can show peaks and valleys in the datascape, or rather, the contentscape. For example, the Blackaeonium archival system data can be used to identify elements like most popular tags used to describe objects, or to identify objects that have no ‘parent’ object, thus identifying the originating object in a related group of objects.

While the Blackaeonium archival system does have structured system metadata, gaining access to content via metadata alone has limitations. The metadata in the archival system relates to different types of information necessary for describing and accessing the item in the archive – format metadata, rights management metadata, contextual metadata, etc. This information may be dry and technical in nature. The ContentDescription field in the Blackaeonium archival system allows for a more freeform text description of content, and may contain both functional and literary elements, making it a more creative means of accessing items in the archive, but even this descriptive text has its limitations.

Through the formal “metacontent” relationship in the Blackaeonium archival system, any object in the system can become a metacontent object for any other object in the system. This increases the possibilities for deriving meaning for content objects in the assemblage where metacontent is not only text - it could be image, video, audio or some other format.

A feedback loop can also occur if two objects are linked as metacontent for each other. One metacontent object could then be substituted for another if an object is inaccessible for any reason thus preserving and making accessible the content within the objects. The image in Figure ?? is an example of this – the still image is one in a series of static works, but it is also a frame from a piece of video footage used in two other works, and therefore is also metacontent for the video work, and visa-versa.

This research is working with the idea that multimedia metacontent (not just textual metadata) can construct narratives, and can create memory, meaning and significance for content that we have lost the ability to access over time through lack of appropriate technology or calamity – as demonstrated by documentation in the archive of a project called “Narcisse Revisited” (see section 2.1 for a more detailed description). The documentation consists of video footage metacontent of content in the archival system using obsolete browser software. The multiplicities and recursions that have developed through working with multimedia metacontent as a part of this project are a compelling area to research in the current creative environment where the archive, remix and glitch as art forms are being widely debated.

Many of the cultural initiatives for preservation of digital media recommend using standard digital file formats for documentation of variable media works where the original artworks cannot be preserved, or are preserved but in an inaccessible state. This is currently acknowledged as the best way to preserve the meaning and the knowledge of these works.

With this in mind, I thought it would be advantageous from preservation and creative perspectives, to use this method of documentation with standard formats as “metacontent” to provide information about works that are for some reason inaccessible, or that I anticipate will quickly become inaccessible, for example: the Flash code-driven animations like the Colour Fields series. This method then, also provides creative means to keep working with the content, concepts and themes in the previous works, to create new works, and the cycle continues – this is the continuum mode that is the main focus of the creative practice established through the research.

This method of documentation is not a new concept, but a concept taken from the preservation field into the artistic field. In the Blackaeonium archive, The metacontent can be documentation, it is also in some cases migration to different media, it is also in some cases re-presentation as preservation – where the migrated media has been used in recombinant and remixed artworks, and has informed the development of new works. It’s through this method of combining the archival and the creative that artists may best be able to preserve the content they create and the intent for that content to be accessed, presented, and understood. The Blackaeonium archival system becomes a propositional artwork that tests whether the slow remix underway in the personal creative archive, can enable a method of preservation through using the archive creatively.

In archives and records management, it is understood that items frequently accessed and used in administrative and business transactions will have a longer life span than those not required to satisfy organisational functional requirements. In layman’s terms, using and reusing items in the digital archive keeps them live and alive for longer. If we need these items, we will work harder to ensure they are accessible, we will upgrade their software formats, we will make regular backups and ensure they are easily retrievable.

If the artist continues to require certain material in the archive, then the same will happen for creative content. This is something that occurs naturally through creative practice – we artists all keep our visual journals handy. Those of us using digital media in our arts practice walk around with heavy external hard drives in our handbags and backpacks. We make endless copies of the files we need, we put them online in “the cloud”, email them to ourselves, put them on our blogs and websites. We are desperately afraid of losing work – especially those current projects that are developing daily.

By selecting the essential content that we need to keep our creative practice going, by archiving the “vital” content in one central location, then this “natural selection” can happen in a structured environment, and we can document this work with some kind of methodology in place. By creating better practices for the material we need at hand in the present, we are simultaneously giving it a better chance of being accessible in the future.

I know that in my own variable media practice, when working with digital projects like the Colour Fields series, when a project version is “complete” or at least functional and ready for exhibition, I may choose to delete some of the versions I was saving “just in case” I had to go back and reverse some unfortunate coding error, or aesthetic decision. I naturally go through a selection process, and I don’t keep everything. It would be impossible to keep all the versions of rich media projects – mostly because of the nature of the video format and the size of uncompressed files, but also because the more files I have to manage, the harder it gets to access the required material immediately.

I chose to create the Blackaeonium archival system to document and store only those items that were essential to be able to reconstruct my arts practice, to trace the creative themes and concepts that form the main body of work that represents my practice, and to keep those items I think (at the time of making an archival act) that I will want to use again in my work – whether it’s just for reference of an idea or whether the item can actually become part of something new.

Preservation and Decay

It is alarming for the creative practitioner to experience how quickly content can become inaccessible if working with software applications and “bleeding edge” technologies. It constantly requires migration or reinterpretation of new media works that must be kept accessible.

Many examples of this exist in my own Flash content that is only 3 years old. I am currently migrating this content to a newer version of the software application because of how elements like webcams, browsers and the Flash player (within the browser) deal with the content. Also, many users have faster computers with more RAM, memory, CPU power and all this affects how some of these artworks function – I have realised that in my original development of certain Flash-based works, I should have used a timer function to control playback speed instead of relying on frame rates to play the work at the desired speed.

There is also the fear now that Flash may soon become obsolete, taken over by new developments in HTML5, CSS3 and jQuery/JavaScript that allow for more interactive and media rich websites without proprietary plugins like Flash. This is a current problem because the specifications for HTML5 are not yet finalized, nor are all the web browsers we rely on to serve us this content, working in a standard way. Artists like myself require applications like Flash to achieve the effects we want, but are mindful of the closed nature of the code, and the possibility our works in this media format will soon be inaccessible by most people – anyone using a Macintosh iPod, iPhone, iPad already knows this.

The way I currently combat this dilemma is to continue to use Flash, whilst also using a product called Moyea SWF2VID to capture portions of the code-driven animations as video. It’s a poor alternative, because the very nature of the Flash works being endless and never showing the same sequence of pixels twice is completely destroyed by turning a 10 minute portion of it into video. It then becomes the same sequence of pixels playing over and over again, with a definite starting-point and ending-point.

The video is in some ways a poor substitute for the code driven animation, but it at least provides a sense of the work, of the colour, the slowness, the layering of content, the accompanying ambient audio. This method of preservation is at once, storage, migration to another format where possible, and re-presentation using another type of media. The documentation of artworks becomes the means of understanding the artworks. This is nothing new in archival methodology, nor in variable media preservation. But in this case, the method is used as a part of creative practice by the artist, thus become a natural method of preservation. Many artists working with ephemeral and variable media already do this, but like many creative practices, they are not explicitly recognised as preservation methods, and have not been considered central to the creation of artworks.

The video metacontent has been useful to capture beyond the immediate preservation issue, because for certain group exhibitions, or calls for new media artworks, cultural organisations tend not to have the means to display code-driven animations. They usually ask for video works or still images. It’s disappointing in this day and age that this situation is still true. It is most unfortunate for those of us working with code – so well described in the text by Martine Neddam (2010). It is still difficult for many contemporary cultural organisations to exhibit live, complex, variable media works that don’t fit into constrained media formats. If this is the case, how will they ever be able to manage preserving them into the future?

Redevelopment or even reinterpretation of some of these works in newer software or different software to achieve a similar visual effect is already necessary. Video footage has already been captured from some of these Flash projects; to both act as metacontent for the original works, and also to become new video artworks in their own right. The recombination and recursion continues as the video footage may then be used in another Flash file to create another interactive work... a continuum and recursion of content and metacontent.

Reinterpretation is seen as risky when not undertaken by the creator of the work due to possible misinterpretations, but as individual artists, reinterpreting our own content could be an exciting creative process to undertake – the archiving of Lyndal Jones’ “At Home Series” (1977 - 1981) is an example of this – digitisation and archiving of the content into an interactive website allowing for potential new re-interpreted artworks in the form of recombinant remixes, print publications and gallery exhibits. Reinterpretation is a method for the creation of substantial metacontent for works that are difficult to preserve in their original form – as both documentation of the original, but also as another way of keeping the content alive and accessible, leading to the creation of new works.

This research is investigating what might happen when contextual documentation and related metacontent go beyond the original object, i.e., reinterpret the original object, and become something new or different.

The Web forces us to reconsider what we mean by preserve and archive. When everything becomes an archive, when a colossal amount of information is a mere mouse-click away, the meaning of archive shifts from accumulating and storing information to navigating, to jumping between different links, to mapping, and to pinpointing relevant information. […] To make accessible – and to access – is to preserve. […] Preservation and the commitment to long-term access are now inseparable. There is no preservation without dissemination. Moreover, on some sites, the content we access exists only for the moment of access. Thus, in a way, the access itself allows the content to exist. (Depocas 2001, p.3)

languages and applications currently being used are likely to become obsolete. The system needs to contain self-documentation, and must be able to output its own content to another system or format. Who will ultimately store or host the system? Where will it be hosted? Must the artist rely on some collecting institution to incorporate it into their collection? Would the artist want to take this approach and would anyone else think it valuable anyway?

For artists, maintaining a single keeping-place or repository where documentation of all the content distributed across blogs, Facebook profiles, Second Life residencies and other online systems could mean that even if the third-party site is removed from the Internet, is destroyed, or is fundamentally changed in some way that is out of our control, then we may still have metacontent documenting what happened, and what the environment was like on that site.

I have tiered works of my own that have developed over the past few years. Some works held on my website are also held on or linked to other new media sites such as Rhizome.org (2007) PAM (Perpetual Art Machine 2006), DVblog (2007), [R][R][F]200x—>XP (2007), Virtual Art Space, (2011) JavaMuseum (2011) and Electrofringe (2006). Some of these works have also been exhibited in physical spaces as video installations. I choose to keep significant versions of these works, and metacontent/documentation about these works in the Blackaeonium archival system. I can also document how they exist or existed on the other sites – such as capturing still images in Second Life and placing them in my archival keeping-place. The Blackaeonium archival system is the most stable, accessible point of entry to all of these works and sites or time-space locations whether physical or virtual, analogue or digital.

Occasionally I even take screen captures from my Twitter “favourites” feed on my home page and add these to the archive – they have a recombinant poetics all of their own.

Keeping Content, not Object

The research for this project began with investigations into preserving digital objects, but as the project developed and the research continued, it became apparent that it is the preservation of creative content which is of specific interest. The digital objects themselves have no real intrinsic value as files or as formats – they can be reproduced, copied, migrated, emulated and reinterpreted.

This is a different approach to the preservation of analogue objects that cannot be exactly reproduced, although one may find similarities in analogue methods of capturing and documenting content in formats other than those used for the original. Examples of this analogue content include formats such as a photo of a painting, an engraving of a sculpture, a 16mm film depicting a live performance on stage, a score for a piece of orchestral music, or a script for a play.

A consideration for preservation strategies for artworks has been that certain variable media works are specifically about the media format and the technology being used – the media is the content in these media art works. Some artworks must use specific technologies, and must be executed at certain times and physical (or virtual) locations, and once executed, no trace or very little trace may remain.

In the case of my own work, the content can exist in many formats, both analogue and digital. There are endless possibilities in taking content into different formats and multiple formats at once. It was necessary, however, to examine whether the methods and tools being created could somehow facilitate capturing works that cannot be transferred to other formats. In fact, this is not possible with the current web technologies used in this research project. There are limitations in the system. The decision was made to take the approach that in some cases, to be a keeper of content, it is necessary to be a documenter of that content or the events that produced the content rather than a re-interpreter, emulator or migrator of objects.

This is not strictly ‘preservation’ then, as it acknowledges that some works are lost as soon as they are created. We may only capture a trace of them, and document them as best we can. I accepted the idea of loss as a part of the idea of keeping before the research even began – the project is an endeavour to deal with both what we lose and what we keep. It is not possible to completely prevent loss when dealing with media arts that have multiple and complex formats and contain temporal and spatial elements.

Creative content could be seen as something transient, ephemeral, evanescent, maybe even sublime – it is the keeping of that subtle stuff that artists create which is a primary focus of these investigations.

I have always had a personal interest in the so called “support works” of artists – sketches, drawings, texts, incomplete developmental works, etc. I am drawn to these works – sometimes more than the “finished work” – perhaps because these developmental works often hold raw conceptual content, ideas and traces of process, and I find these elements compelling to engage with. These items form part of the documentation and preservation of creative content in the Blackaeonium archive.

Capturing concepts and documenting them has been one area of investigation for the research project. The Blackaeonium archival system is a space to document projects yet to be created, as well as projects that are underway or complete. It contains text files and sketches of ideas not yet developed into finished works. It has also been used to document content such as a recipe for a specific colour of indigo ink made from 5 different types of off-the-shelf inks. The ink recipe is valuable metacontent to many works that use that specific ink. An example of this are the diary pages added to the Blackaeonium archival system documenting a concept for an interactive work ‘The Crying Game’ that has not yet been developed.

Certain methods and processes used in this research project could share the same concept space with the Fluxus Performance Workbook (Friedman et al. 2002), which contains scores for performances that may or may not have been performed, or that anyone could perform at any time or place. It could also have a conceptual relationship to the Deep/Young online project titled _This concept (Deep/Young 2007), which invites people to submit concepts to an archive website for artworks that do not exist. The artworks have never actually been executed.

Although the Deep/Young project is satirical to some extent, and a comment on conceptual art, it has validity as a concept in itself. Capturing concepts and documenting them whether they become finished works or not can still provide something valuable for the artist as a reference point, and for long-term archival purposes documenting an artist’s processes for developing creative concepts.

The concept of metacontent developed through this research is essentially about keeping content in a variety of formats to facilitate preservation, and to form a kind of memory pool for facilitating the development of new creative works. An important focus of the research is to create a more comprehensive picture of the content in context and in relation to other content, thus forming an interconnected collection or assemblage of content objects.

The Development Cycle

System Testing

Testing involved adding data and content to the online system to make sure all of the configuration settings were appropriate for uploading a variety of media types and file sizes, noting any bugs and recording system errors for modules not functioning properly. It also involved repeated user interaction with the system – performing searches for content and thoroughly testing every possible interaction with the system to make sure each code element was working properly.

The system also has a password protected administration area where system specific data is entered, and documentation for content objects is inserted, edited and deleted. The security measures and session management required to create this part of the system also required strenuous testing to make sure protected files and data were not accessible to the public. This testing was conducted by trying to access all parts of the system with and without the necessary usernames and passwords, to try and circumvent conditional statements in the code developed to prevent malicious attempts to access protected content.

Printout pages

of interfaces were used as checklists for testing. Decisions were made based on

qualitative testing outcomes regarding measures to be taken to improve system

functionality and security, and on the perceived requirements of the artists

involved in the documentation process. Improvements are constantly being made

to the system based upon these decisions. Testing is an ongoing process, and,

constantly changing technologies may render aspects of the system

non-functional. There is an ever-present need to keep updating the system. And

this happens on a regular basis through constant use of the system in the three

iterations of it that are still evolving (Blackaeonium, At Home and Atemporal).

Evaluation of the overall project and outcomes produced

By working with a practice-based research methodology, and the archival system and methods developed through the research, my creative practice did change over time. The actions of documentation and placing objects into the keeping-place began to affect the new works that were created. By reflecting on the content in the system (documented in the blog), and experimenting with recombinant works in the system, interesting themes and patterns were discovered within my work that had not been apparent before, and these were then used in the creation of new works. This also enabled re-evaluation of themes and concepts already known, thus enabling me to push these elements further. Evidence of these discoveries can be seen in works such as Unmade and Colour Fields - discussed in Chapter 3

The evaluation of the project is qualitative and continuous, involving ongoing user interaction with the system to upload content, develop metacontent, and experiment with generation of recombinant and new artworks from the system. A range of recombinant and new works were developed throughout the research project.

Successful system development has been determined through qualitative analysis to assess whether the artist participants and main archival documentation creators (myself included) are able to access and engage with the content in the archival system to store content and present artworks (whether new or recombinant). This engagement with the system was observed to examine usage both by users outside of the research project, and the creator-users themselves to see how artists may use the content in the system to enable self-reflection and analysis of creative practices. The documentation of creative content and artworks tested the system functionality, but user testing from an audience-user perspective has also been conducted to see how an audience might engage with the content in the archival system and to receive suggestions and recommendations for improvement. Outcomes of this are discussed in Chapter 4.

The aims of the project were determined as having been achieved when the Blackaeonium archival system was complete enough to allow for most of the proposed functions to be operating without error, and when recombinant and new artworks were being generated through use of the system. The quality of the documentation, the content and recombinant displays have been determined through user-testing with the artist participant users – the artists as case studies in the use of a personal archival system, and non-participant users (audience) - a small group of artists, digital media developers, archivists and lay people that were able to engage with the artworks and creative content of the artist participants through the archival system. By accessing the artworks, or by becoming “guest remixers” and engaging with the content in a more influential way.

Informal interviews with structured questions were conducted to observe users interacting with the system. Feedback was collected in three main areas:

1. The archival documentation input (which requires a small amount of training and instruction from the project archivist/system developer)

2. The artist participants using, interacting and engaging with their own content in a creative and meaningful way; and

3. Guest remixers.

4. Non-participant testers (artists and digital media developers) engaging with the creative content as an audience-user or reader-user of the artworks.

A set of nine questions or “considerations” were developed for user testers based upon reading Jakob Nielsen’s website “useit.com” (Nielsen 2010) and Ben Schneiderman’s “8 Golden Rules for Interface Design” (Schneiderman 1997). These questions were developed to specifically suit the purpose and function of the Blackaeonium archival system as an online archive and an artwork or creative project.

Online surveys were also developed to collect feedback from different groups of users

(See Appendix 5: User Testing and Guest Remixes Questionnaires & Surveys).

Presentation of research outcomes

Presentation involved publication of the system on the Internet and linking artworks created through this research to relevant websites and portals such as the Rhizome.org Artbase (Rhizome 2007), Perpetual Art Machine (2011), JavaMuseum (2010), DVBlog (2007) and Virtual Art Space (2011). It also included presentation of the research project at the 2010 Australian Archivists conference and presentation/exhibition to peers and the general public via web publication allowing users to view and interact with the system, or to view selected art works that have been derived or conceived from the research project. Presentation also occurred in the form of physical exhibition of selected works in two galleries – Obscura Gallery “Group Exhibition” at Obscura Gallery 2011, and Level 17 Artspace “Aura: The Haunted Image” (Victoria University 2011) in March/April 2011, the Colour Fields exhibition at Obscura gallery in 2011, and the MUMA exhibition “A Different Temporality” in 2011 This phase of the research is an iterative, ongoing cycle of creation and presentation, and will continue into the future as new works are created, more content is added to the system, and the system is linked to more sites and portals to enable further proliferation of content over the Internet. Many exhibitions and presentations of content currently under development in the Atemporal project are planned for 2013, and education modules (Future-Proofing for Artists) developed in 2012 are currently being piloted with digital media students at Victoria University School of Creative Industries.

References

See Bibliography and References page for a list of all publications.

Standards & Schemas

Variable Media Questionnaire - http://variablemediaquestionnaire.net/demo/#a=20

Dublin Core Metadata Standards - http://dublincore.org/documents/usageguide/elements.shtml

ISAD(G) - http://www.ica.org/sites/default/files/isad_g_2e.pdf

EAD - http://www.archivists.org/saagroups/ead/index.html

Publications

“The Australian ('Series') System: An Exposition” Author: Chris Hurley, in The Records Continuum: Ian Maclean and Australian Archives First Fifty Years, Sue McKemmish and Michael Piggott(eds), Ancora Press in association with Australian Archives, Clayton, 1994, pp. 150-172

Seaman, William Curtis (Bill) 1999, Recombinant Poetics: Emergent Meaning as Examined and Explored Within a Specific Generative Virtual Environment, PhD Thesis, Centre for Advanced Inquiry in the Interactive Arts, University of Wales, viewed 21/06/2010

Australian Government Record Keeping Metadata Standard Implementation Guidelines, National Archives of Australia, version 2.0, June 2011

top of page | homepage & table of contents

[1] The Multimedia Resources Database System (MRDS) was a quasi archival/content management system (data-driven website) which formed a small part of the greater content management system used for all training package materials in the Digital Media Program at Victoria University, of which I am the key developer. While the greater content management system is still in use and has been widely successful, meeting all audit requirements, and receiving an award for Innovation in Education in 2003 from Victoria University, the MRDS system ultimately failed to meet its original purpose due to lack of use and reluctance of staff to enter data into the system. (Cianci, 2003)

[2] “ ‘Born

Digital’, digital materials which are not intended to have an analogue

equivalent, either as the originating source or as a result of conversion to

analogue form.” (Digital Preservation Coalition 2002)

[3] A permalink is a permanent URL link: “Permanence in links is desirable when content items are likely to be linked to, from, or cited by, a source outside the originating organization. Before the advent of large-scale dynamic websites built on database-backed content management systems, it was more common for URLs of specific pieces of content to be static and human readable, as URL structure and naming were dictated by the entity creating that content. Increased volume of content and difficulty of management led to the rise of database-driven systems, and the resulting unwieldy and often-changing URLs necessitated deliberate policies with regard to URL design and link permanence.” (Wikipedia 2007g)

this page produced by lisa cianci on her website www.blackaeonium.net

comments and queries to lisa's email address on scr.im (for humans only)

created 01/12/2011

last modified 30/07/2012