homepage & table of contents >> introduction

Introduction

After the current tempest, what deserves to be archived and what must be archived? What is best to be forgotten? What should we include in our archives for their perseverance? And above all, in what way should we construct our memory? Although these questions are common to all kinds of data, information, objects, events, etc. in our culture, they are especially relevant in the context of artistic and cultural productions linked to electronic and digital mediums. (Alsina 2010)

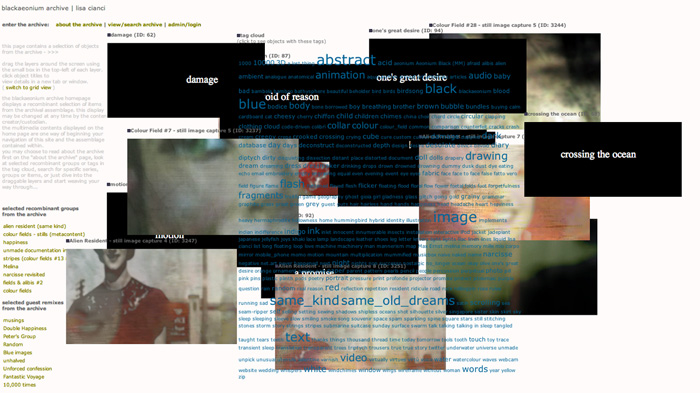

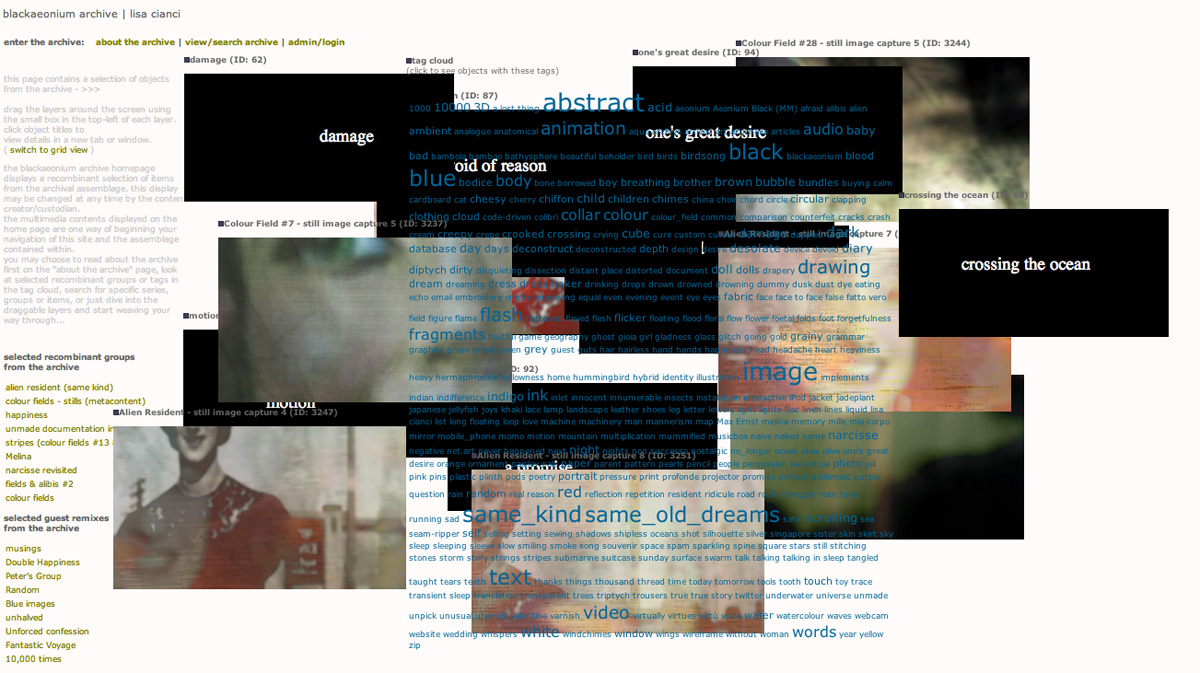

Figure 0.01 Blackaeonium Archive homepage, Lisa Cianci 2012

(click to view larger image)

About the Blackaeonium project

The Blackaeonium research project involves the creation of an online system to store elements of artworks as an ongoing personal archive that also works as a creative framework for continuing development of new artworks (Figure 0.01). The research is focusing on the empowerment of artists in the control and management of our own creative content. The system purpose is twofold:

- the preservation and documentation of artists’ work by incorporating elements of archival science (and to some extent curating) into creative practice (The archival act).

- the provision of ready access to the archived elements of these works by artists to recombine and remix them in the creation of new works, proposing the idea of an archival assemblage as a slow remix [1] (The creative act).

Use, reuse and keeping content live (online) and alive over time may be a method of preserving it for longer. Preservation methods for digital media such as storage, emulation, migration and reinterpretation [2] may happen naturally in creative practice through content that is reused, remixed and re-presented via the online, digital archival assemblage[3].

the contemporary remixologist

will always source the distributed "mind bank network"

as a "cite-specific" living archive whose data is open

to improvisational revision and transmedial postproduction

(Amerika 2008)This research is partially a response to the increasingly urgent activity surrounding the development of a range of digital preservation strategies and systems by cultural institutions, recognising that much of our cultural and creative works will otherwise become lost forever. Initiatives such as PANDORA (National Library of Australia 2006), the Variable Media Network (2006), Circus Oz Video Archive (2012), Rhizome.org Artbase (2007), the DOCAM Research Alliance (2012), and the British Film & Video Study Collection (Central St Martins College of Art & Design 2012), are examples of some of the varied projects that have been dealing with these strategies.

There are issues that arise when considering these cultural initiatives:

Artists don't have ongoing access to the strategies and systems developed by many of these initiatives. Cultural organisational stakeholders develop them largely for preservation and access of items that form their holdings. They may receive finite or limited funding to undertake such preservation projects, and the scope may be quite narrow. Fortunately, artists are increasingly being involved in the preservation strategies for our works – as with the Variable Media Network Initiative, but these strategies are driven by these cultural organisations, therefore, artists are affected by organisational changes that may impact on preservation operations.

Artists often receive no benefit from the commodification and objectification of their works by these same cultural institutions. It is difficult here to reference specific examples, but the net.art and variable media email list communities are rife with impassioned discussions on the topic of artistic freedom, and the many problems in this area. One thread of discussion that can be mentioned is a series of email posts on the empyre email listserve where academics such as Melinda Rackham and Jon Ippolito have engaged in discourse under the title of “gift economy v art market” (Empyre 2002), outlining many of the ways in which artists are affected by institutional and commercial factors [4].

There is a tendency for contemporary artists to recombine and remix earlier artworks and creative content in order to create new works. Examples of this form of creative practice are easily found. To mention a few well know Australian artists, one only has to look at the work of Rosslynd Piggott, Imants Tillers and Juan Davila - artists who work in quite different ways, but all base their practices around reoccurring concepts and preoccupations: Piggott’s work, especially the installed works from the 1990s, use and reuse similar themes and imagery around the concept of “suspended breath” (Coates & Williams 2008) – capturing and cataloguing air in vials, which is an element that develops over time, through many of her works; Tillers works with themes and imagery relating to migration, displacement, landscape, and he frequently remixes content in his work in the post-modern way referred to as “quotation” (Hart 2007); Davila’s work also uses quotation and reference to other artworks including his own works, to create a confronting critique on sex, culture and politics (Briggs 2011).

The artists cited above are painters, object makers and installation artists. Many contemporary artists working with digital media also consciously recombine and remix content. Artists such as Francesca Da Rimini, Occulart, Martine Neddam and Mark Amerika create works with digital media. The variable nature of their work will be discussed in Chapter 1. On Recombinant Poetics, Virtual Spaces, Remix and the Archival Continuum: an overview of the fields of practice and conceptual foundation for the project.

I propose that artists may benefit from consciously incorporating preservation strategies into our own art practices in a way that is immediately useful to us (useful in creating new work, in connecting with other artists and engaging an audience), and has value in the future to potential stakeholders.

Furthermore, I also propose that artist education in preservation of variable media is of value to our field of practice – in order to empower artists to choose suitable strategies and systems if they are made available.

The Blackaeonium Project has been undertaken to demonstrate the potential of empowering artists to conduct our own documentation/archival practice within our creative practice. The artworks and supporting content developed through this research have followed a set of processes and methods developed by understanding and gaining knowledge from working in multidisciplinary fields of practice, and from the creative act, the archival act, and the practice-based research methodology that underpins the entire project.

Proposition

It is proposed that meaningful and deliberate keeping and documentation of selected content, and the creative act of recombination that happens through juxtaposition, remix and experimentation with content elements [5], can be harnessed as a method of preservation using an archival continuum framework [6] to make this process more explicit through documentation. This will be tested through the Blackaeonium project.

Research Questions

- What elements from archival science (and archival curatorial practices) can an artist use on a daily basis to improve the quality of self-documentation, to future-proof creative content and make explicit an artist’s intent for the presentation of artwork?

- By building archival elements into a creative practice, how might this affect the creative practice itself, and what new works might be able to be produced?

The aim of this research project is to test the proposition by creating an experimental archival system prototype suitable for artists. The research questions will be answered by using my creative practice (and that of others) to submit creative content and artworks to this archival system, and to develop new works through this practice.

About the name "Blackaeonium"

Blackaeonium is the name I have given to my domain where the database-driven archival system prototypes developed through this research are hosted. The project and the systems have been given this name too, and will be referred to as the “Blackaeonium archival system” throughout this exegesis. Black Aeonium is the common name for a type of succulent plant - Aeonium Arboreum Var Artopurpureum 'Schwarzkopf' [7].The Blackaeonium archival system is an experimental archival system prototype created to allow for the experimentation intended through this research. It can be described as “workspace/keeping-place” due to the duel function of the system: it uses the archive as a workspace to provide the impetus to keep and document creative content (a task that can be regarded with resistance - a chore to undertake); and it creates an archival space for play and experimentation, for the artist to work creatively in the archive.

Context: importance of the research

Artists are not generally good at documenting and preserving creative work.

In the arts focus case studies, whatever metadata-related practices there are tend to be idiosyncratic, ad hoc and at the discretion of individuals working with the system. Any metadata standards being implemented have been developed for resource description, discovery and use purposes and not with a view to ensuring the long-term preservation of authentic materials.(InterPARES 2 2006, p.302)

Evidence of this was gathered during this research from initiatives such as InterPARES 2 (International Research on Permanent Authentic Records in Electronic Systems (InterPARES) 2: Experiential, Interactive and Dynamic Records, 2006), the British Digital Lives Project (John et al. 2010) that examined personal digital collections, and Archives2020, a Virtueel Project forum from the Netherlands where “the most urgent problems are discussed and a plea for sustainable archiving of art and culture is made” (Dekker 2010).

The texts and project outcomes produced by these initiatives clearly demonstrate a need for strategies – not only for artists, but for all areas of creative practice. These initiatives will be discussed in detail in Chapter 1, as they were all useful touchstones to compare my own creative practice and experience as a creator of digital, variable content (and that of my peers) with what is happening at an international level.

As the InterPARES 2 report states, many artists may not be aware of the risk of loss in their current practices.

Despite the advances in digital preservation research in the last ten years, there is still a remarkably low level of awareness of the risks to cultural heritage material in the private sector, which falls outside the domains of academic libraries, archives and government.

(InterPARES 2 2006, p.288)That sense of urgency to preserve variable media works, can be seen in many cultural organisations and initiatives such as:

- The Variable Media Network founded by US scholars from several cultural organisations to pair “creators with museum and media consultants to imagine potential futures for works in ephemeral formats” (Variable Media Network 2006);

- DOCAM (Documentation and Conservation of the Media Arts Heritage) Research Alliance founded by the Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science and Technology (DOCAM 2012) to research and propose solutions for the preservation of media arts;

- The Rhizome.org Artbase (Rhizome.org 2006) which stores artworks and links to variable media artworks from an online repository and portal space;

- The many cultural collecting organisations such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, which has an active preservation program - the Contemporary Art Archive, that “gives attention to experimental, ephemeral, performative and investigative art practices through the acquisition of lesser known aspects of artists’ activities.” (MCA 2012);

- Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI 2012) ; and

- PANDORA - Preserving and Accessing Networked Documentary Resources of Australia (National Library of Australia 2006), a collection of Australian online publications.

Cultural institutions and organisations are currently addressing problems of preservation, authenticity and presentation of variable media artworks and related creative content. My own background in archives and information management has provided a level of awareness of these issues, therefore this project has been undertaken in recognition that these issues are important for all artists to know about.

I propose this research to be necessary as an adjunct to institutional and more general research in the field because it investigates possible ways for an individual artist to minimise loss of creative content – without (or before) intervention from cultural institutions and organisations. Many artists are not “collected” by a cultural institution, and if they are eventually “collected”, there may already be substantial loss of content or lack of authenticity in their personal collections.

I have identified an archival strategy for artists to possibly include:

- maximizing access to content (resource discovery and use is necessary for the artist at the point of creation and in “the studio”); and

- making explicit the artist’s intent for their work over time – irrespective of custodian (the artist, or a future stakeholder), thus improving preservation, authenticity and understanding of the artworks.

A recent example of the relevance of this for the artist is the 2011 exhibition at Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA), “A Different Temporality: Aspects of Australian Feminist Art Practice 1975-1985”(McFarlane 2011). Many of the variable media works (video, mixed media, installation), and documentations of ephemeral performance works all created/performed in the 1970s and 1980s that were shown in this exhibition, are held by the artists. This exhibition provides insight into an important period of time in Australian art, including central works by Micky Allen, Jannet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley, Bonita Ely, Sue Ford, Helen Grace, Lyndal Jones and Jenny Watson.

Some of these artists may have archived selected works in collecting institutions (as with Lyndal Jones’ Prediction Pieces (Cramer & Jones 1992), works by Bonita Ely at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney), and works by Micky Allen at the National Gallery of Victoria, but the work in this exhibition brought a significant aspect of Australian feminist art to the fore, and also to a new audience, only available because the artists were able to physically provide it.

I wondered if after the exhibition, these important artworks would just be packed up and sent back to their creators? Will these artists continue to maintain their artworks as they have done over a significant period? What will happen to them in the future? All that remains for the public audience now is the exhibition catalogue.

It is fortunate that these artists have kept their work for so long, but it was the curation of the exhibition at MUMA that provided access to this content – and only for a matter of weeks. Aside from the exhibition catalogue, there is no ready access to these works - except for Lyndal Jones’ At Home series, digitised and archived in a Blackaeonium archival system as a part of this PhD research project (Jones 2011). This example provides tools for artists to use themselves. This demonstrates how educating artists in understanding the potential risk to and loss of variable media artworks may benefit not only the artist, but also the audience in accessing and engaging with creative works over the long term.

Recent and ongoing research projects have informed this research project. In particular, academics and professionals involved with the initiatives mentioned previously have investigated the preservation of artistic and creative content from curatorial and archival perspectives. The research from these initiatives provides strong evidence demonstrating a great need for better documentation and preservation of creative works – with maximum input from the artists.

The Variable Media Questionnaire (VMQ) developed by Jon Ippolito and other members of the Variable Media Network and the DOCAM Documentation Model developed by the DOCAM Research Alliance, currently appear to be the most appropriate and successful tools or aids in addressing specific artistic intent and requirements for the [re]presentation of their artworks, but the impetus to undertake the questionnaires and document the work usually comes from the curator or collecting institution.

About the creative works produced through the Blackaeonium project

The creative works produced through the Blackaeonium archival system (itself the first creative project):

- demonstrate possibilities for working with the archive creatively; and

- pose further questions for creative practitioners to consider for incorporating archival methods into processes for making and documenting artworks and related creative content – from the point of creation, or even before (as shown in the archival (records) continuum model (Upward 2005)).

As a creative and multidisciplinary project, this research can be located in more than one field of expertise as will be shown in the review of the fields of practice in Chapter 1. It seeks to build upon knowledge and practice developed in contemporary art, variable media preservation, digital media, web technologies and archival science. The aim is to investigate ways these fields might converge in a meaningful way for artists and creative practitioners. It also aims to further the work of initiatives like the Variable Media Network, to consider what artists might be able to preserve themselves, to document process, practice and intent for their own creative outcomes – whether finished “artworks” or other kinds of content.

This research project develops my own creative practice through the use of an archival keeping-place as an ambient framework for creativity. There is creativity in the act of keeping, and the decision to keep. What do I choose to keep and why? How do I choose to document it? What can I do with my content now that I have it all together in an accessible location? The ability to use and reuse this content in potentially endless ways is an exciting area to investigate as an artist working with variable media in the current digital environment. This will be discussed further in Chapter 2. Building the Blackaeonium archival system; methods of development, Chapter 3. On using the Archival Assemblage: 9 examples of creation through the Blackaeonium archival system and Chapter 4. On using the Archival Assemblage: working with artist participants.

Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 address my own creative practice and work in the project development that led me to become the first case study for the research. Chapter 4 discusses the use of artist participants as case studies, required to test the research questions with artists that have different practices and levels of experience in the field. Some artist participants have greater recognition in the contemporary arts community, have created large-scale exhibitions at an international level, and create artwork that is complex, ephemeral and diverse in nature – thus a real challenge to work with in an archival sense.

Participants include: the artists Geoff Lowe and Jacqueline Riva (A Constructed World 2010); Lyndal Jones (Jones 2012)[8]; Dr Stefan Schutt (media arts content developer and narrative researcher); Antony Catrice (mixed media artist and archivist at Deakin University); Carey Potter (mixed media artist, painter, designer and object maker) and Greg Giannis (media artist and educator at Victoria University).

Atemporal - a collaboration in archival space (Cianci 2012a) [9] is an ongoing project that involves a small group of individuals sharing an archival space to create overlapping assemblages. The intent is to experiment with keeping and preserving different kinds of creative content, and also create a space for play and experimentation with ideas, concepts, and content – to make new work and explore ways of presenting and re-presenting that work – individually and in collaboration.

The individuals participating in Atemporal come from diverse backgrounds using a range of media from painting to code-driven animation, from narrative research to working with Magic Lantern projections. They have been keen to try out this “archival continuum mode” that I have developed as a means of documenting and creating work, and their participation is helping to further test the research questions, and the processes and methods I have developed for my own practice.

Selected non-artist participants (from the audience) were also invited as “Guest Remixers” within the Blackaeonium Archive as a means of examining user engagement with the content, and with the remix process. Guests were asked to navigate the archival space to find and select items that could then be saved as a “remix group”, with some text added by the guest remix author. These remixes have been linked to various social media such as Facebook and Twitter, and also added as blog posts to the Indigo Aeonium (Cianci 2011) Wordpress site I have developed as an upper level “semantic layer” to proliferate the archival content and optimise it for searching and accessibility[10]. Audience engagement also occurred in a number of online exhibitions such as Perpetual Art Machine, Rhizome.org Artbase, JavaMuseum and DVblog, also in physical public exhibition spaces with the Colour Fields series exhibited in the VU Level 17 Artspace and Obscura Gallery, and Lyndal Jones’ At Home series archive – installed at MUMA alongside printed photographs and artefacts from the collection as a part of the exhibition “A Different Temporality: Aspects of Australian Feminist Art Practice 1975-1985”.

Background: how the project came about

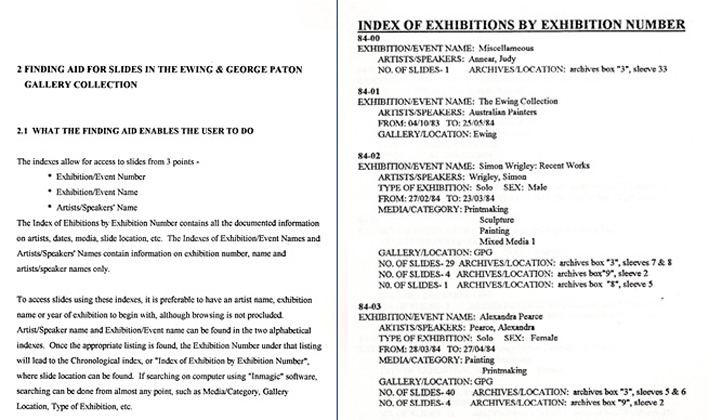

My creative practice originally involved work with analogue media - painting/drawing/mixed media works - from the mid 1980s onwards. I also completed postgraduate studies in Archives and Records Management in 1993, which gave me my first introduction to computers and databases as tools. My research project for the archives course involved the development of a database and hardcopy finding aid, documenting the photographic slides from the Ewing and George Paton Gallery (GPG) at the University of Melbourne (Cianci 1994)[11].

This was the start of a trajectory that involved working as a professional archivist at the University of Melbourne for a number of years [12], whilst continuing my art practice (see Figures 0.02 - 0.04). It was also through the archival work that I gained expertise with digital media, teaching myself database development, web development, and multimedia arts production. I was then employed to teach in digital media, games development and visual art programs at Victoria University. These digital media had become a part of my art practice, so it was a logical step to converge my arts practice with my experience in archives and digital media, to undertake a research project that would benefit artists in some way through using the knowledge acquired from years of work in the field in archives and in developing digital media content.

Figures 0.02 - 0.04 A selection of archival projects that inform the background of this research project.

(click to view larger images)

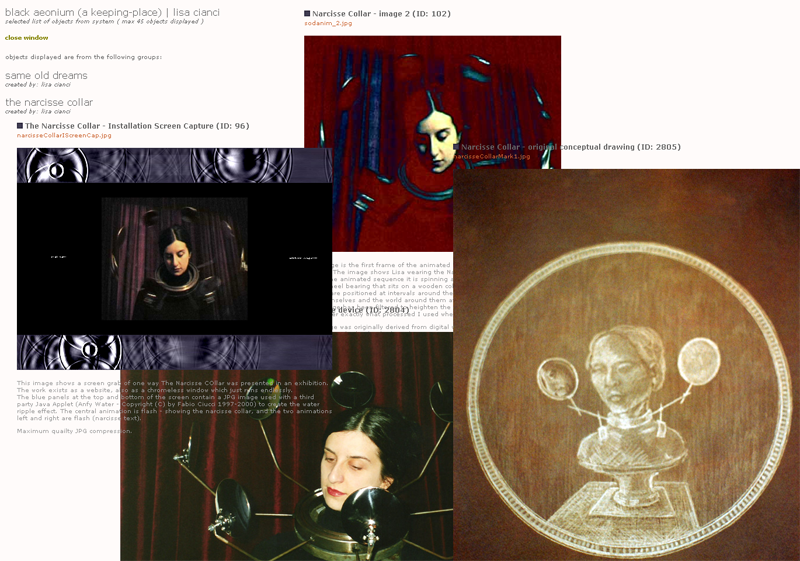

My current art practice involves video, audio, still images and text in interactive works that often use networks, webcams (web cameras) and other digital technologies. I also continue to create analogue works that are installation based, and mixed media works on paper and fabric. I have produced traditional paintings and drawings, interactive Flash animations, installation-based video work, Internet-based net.art projects, database-driven projects, and linear video works (see Figures 0.05 - 0.13 for examples).

Figures 0.05 - 0.13 A selection of artwork that shows types of media from my creative practice

(click to view larger images)

I saw a need for this research because of the multitude of analogue and digital objects (variable media objects) that I was accumulating. It was becoming difficult to organise and find meaning in the gigabytes and terabytes of content being created from digital works and documentation of analogue works [13]. From my archival experience, I know that not all of the content an artist creates is useful; neither does it need to be kept for an extended period of time. We variable media artists must make decisions about what to keep, and some of the content we create has more value than other content. Institutional archives make these decisions all the time. Individuals do too – we are constantly making these decisions, but our decisions are often ad hoc and may not have a process or methodology in place.

The act of archiving is a selective act that I propose becomes a creative one. I choose to place certain content objects in the keeping-place, to document them and link them to other objects in meaningful ways. The documentation and interlinking of objects can generate threads, traces and patterns in the larger body of work. The collection, the archival assemblage that accumulates through this practice can have many outputs, presentations and re-presentations, including the recombinant works and remixes created by interacting with the archival assemblage and the new works that can be conceived from the same interaction.

The body of work I have placed in the archival assemblage is a form of amorphous self-portrait that keeps changing, growing and mutating. It is a personal resource for experimentation, self-examination and an interactive multimedia journal. It is also a place for publication, exhibition, dissemination and proliferation of work. The research project endeavours to take these concepts from a single artist’s personal practice and expand them into methods and processes that may be useful to the field of contemporary art practice and benefit other stakeholders (custodians, curators, archivists, historians) in providing access to artworks with documentation that will assist in meaningful access and preservation over space and time.

Methodology: an overview of methods used in the project

…in creative work, exploratory ideas and acts arise during the process and sometimes as side effects rather than from the explicit objectives being pursued at the time. By their very nature, creative acts cannot be described in advance and this makes the modelling task somewhat challenging. In particular, the application of knowledge that is highly expert, distinctive in character and constantly evolving is a feature of the way creative people work. (Edmonds et al. 2005, p.456)

This research follows a “Practice-based Research”(Candy 2006) methodology, whereby research is carried out through the project [14].

Practice-based Research is an original investigation undertaken in order to gain new knowledge partly by means of practice and the outcomes of that practice. In a doctoral thesis, claims of originality and contribution to knowledge may be demonstrated through creative outcomes in the form of designs, music, digital media, performances and exhibitions. Whilst the significance and context of the claims are described in words, a full understanding can only be obtained with direct reference to the outcomes.

(Candy 2006)Practice-based Research methods have been used to create artworks in a way that followed the dimensions of the archival continuum model, and also in developing the experimental archival system prototype and processes in tandem with the creative content [15].

Hazel Smith and Roger T. Dean’s text “Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts” (2010) was useful in linking my own practice-based research with what they have identified in the field of artistic research. On emergence in artistic research:

currently there is an increasing trend towards documentation and self-description of creative work - as well as growing recognition of the self-critical awareness which is always a part of creating an artwork - whether or not it is externalised.

(Smith & Dean 2010, p. 25)This documentation occurs in the research project – in fact, it is central to the use of the Blackaeonium archival system, and in the creation of artworks following an archival continuum. It is easier to externalise and document our processes as well as our artworks while work is being created in the studio, as opposed to engaging others to try and recreate something after the fact.

The use of an art project is central in addressing and testing the initial proposition because it draws elements of archival science into creative practice rather than attempting to fit what artists do into general archival standards and institutional archival practices. This is important because there is a lack of focus in the fields of archival science and preservation of variable media on artists’ needs at the point of creation, in the studio, prior to artworks being complete or exhibited.

selective processes are at the core of most models of creativity.

(Smith & Dean 2010, p. 23)The Blackaeonium archival system itself is a remix of elements selected from archival systems, digital media metadata standards, curatorial tools, new media artworks and blog systems. It has been created to experiment with a different way of working and keeping content. As Smith and Dean claim, “the rhizome is an interstitial space, open and vulnerable where meanings and understandings are ruptured”(Smith & Dean 2010, p.106).

The Blackaeonium archival system could also be viewed as a rhizomatic, interstitial space where meanings are interrogated and ruptured through access and reuse, through recombination and repurposing of content and metacontent[16]. This relates to the development of the archival system prototype to support the creative practice and why practice-based methods are suitable for this research.

The methods employed throughout the research project were:

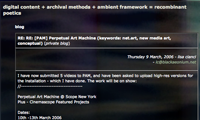

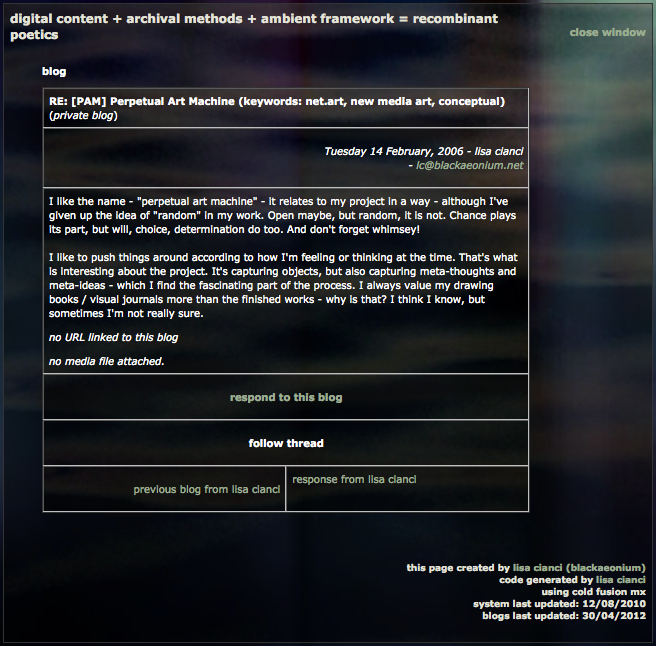

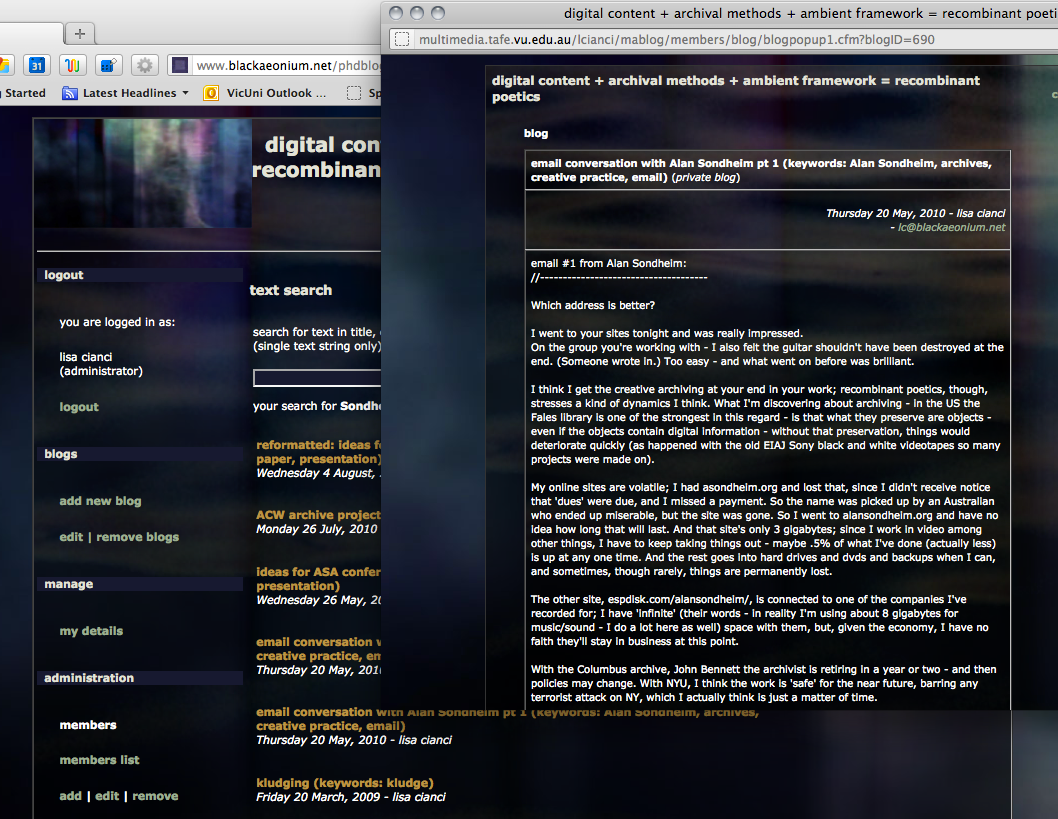

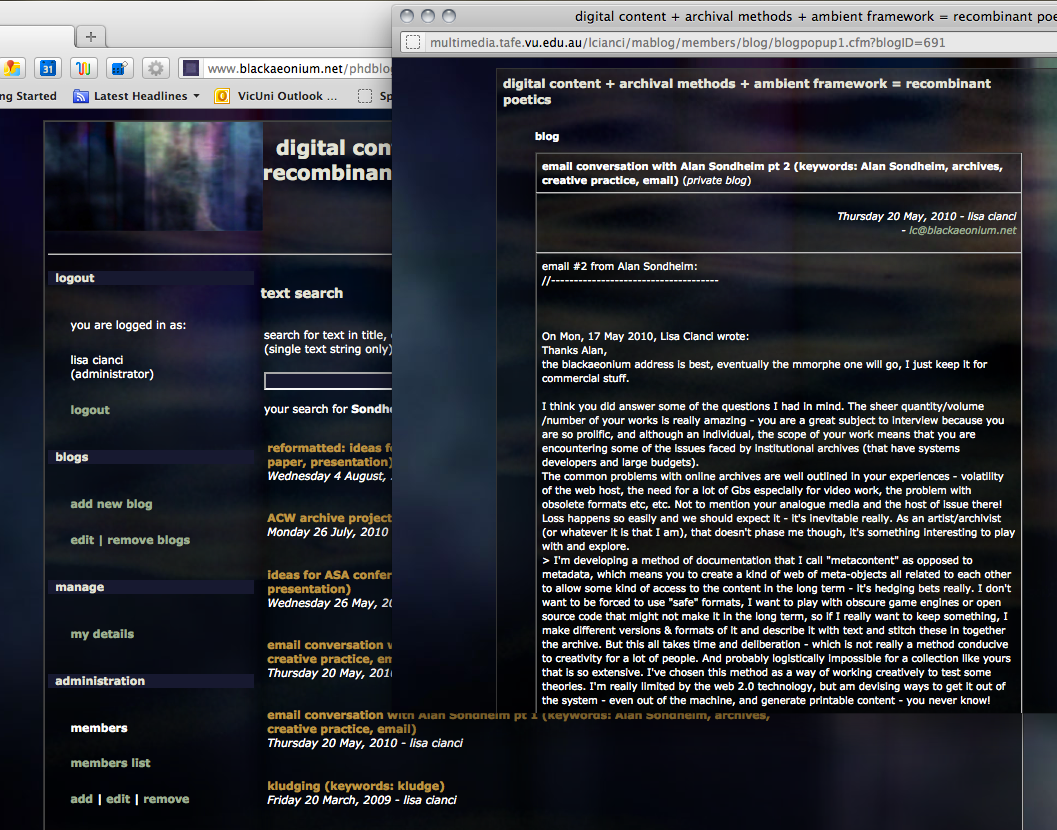

1. The research project blog. This is an important artefact produced as a part of this research and should be recognised as practice-based documentation of processes, development, concepts, thoughts, and a store for references collected throughout the research. I constructed my own blog system in 2004 at the very beginning of the research to enable the kind of documentation I wanted to collect. As with the Blackaeonium archival system, the blog is a remix – part blog, part forum, part group-email client. Initially I developed this system as a group blogging/forum/notification tool for a research project I participated in at Victoria University (Hybrid Initiative (Multimedia/Music Hub) Research Group Blog), and it became invaluable to the project from the very beginning of the research. Functioning in the manner of a “commonplace book” (Johnson 2010, p.83), the blog became a private resource and a central research method with the threading of blog posts as in a forum, allowing for the tracing of thoughts and ideas throughout the eight years that cover the period of the research (see Figures 0.14 - 0.16).

Figures 0.14 - 0.16 Thread of three blog posts relating to my involvement in the Perpetual Art Machine

(click to view larger images)

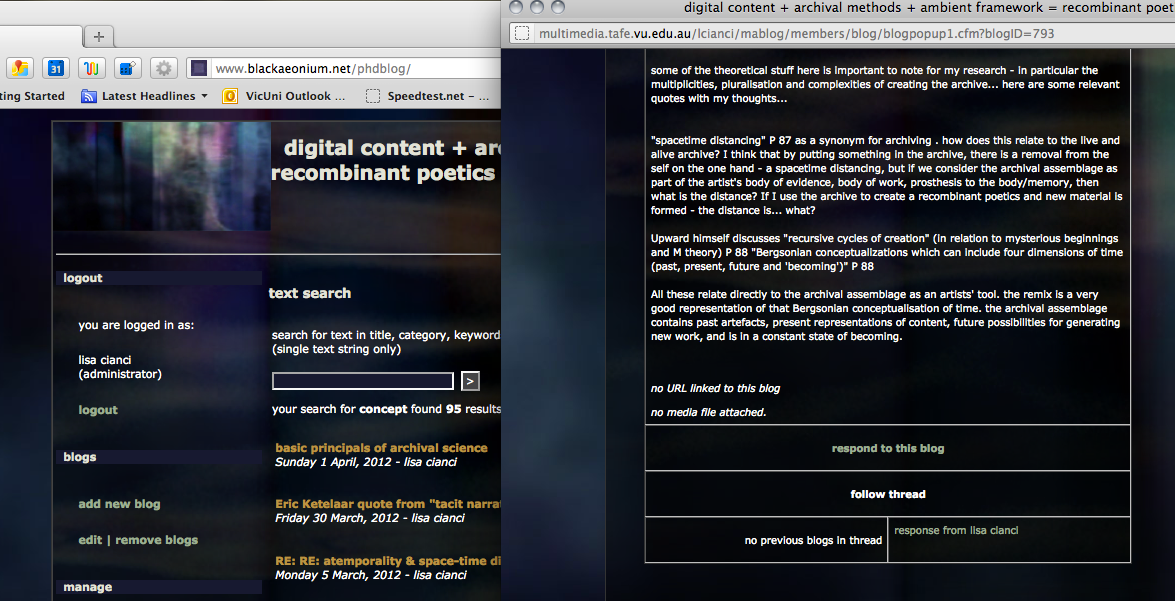

The research project blog contains entries documenting work to be done, work that was done, references to literature used in the research, and links to content developed. Some blog entries are short comments with links to relevant online content; some are lengthy entries with detailed thoughts on various issues relevant to the literature and the project. Some of these blog entries are quoted or referenced in this exegesis (as in Figures 0.17 - 0.19), but any user may login as a guest and peruse over six hundred entries by date or by text search.

Figures 0.17 - 0.19 Thread of three blog posts relating to conceptual development

(click to view larger images)

2. The methods of creating artworks that have developed through my practice over twenty-five years. These methods have been influenced by the studio-based practices of artists that were my teachers: initially as a teenager, painting in the artist’s studio of Desmond Norman, and then at the Victorian College of the Arts in the late 1980s. Methods engaged in the studio for painting and drawing (which were my first creative media), include researching artists and their methods, creating artworks by testing a range of media and processes, reflecting on the outcomes of creative practice, evaluation of outcomes through presentation and exhibition, discussion with peers and mentors, and further development of artworks – often by working on a “series” of works that test a concept, theory or proposition over a period of time, each artwork in the series taking the ideas and processes a little further in the achievement of desired outcomes.

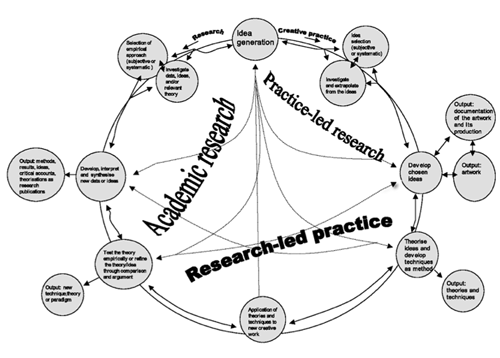

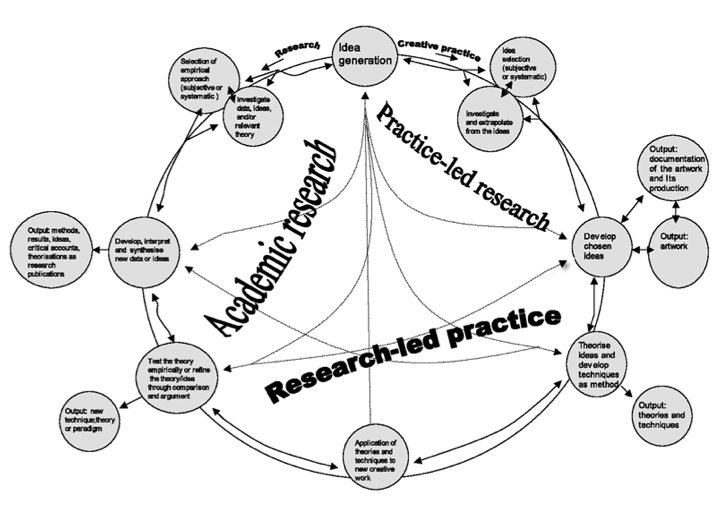

3. Methods that have been learned through studies in digital media in the late 1990s, and in developing a variety of digital media projects since then including websites, database-driven systems and new media artworks. These methods involve a process of research and planning before undertaking the development of the project. An important aspect of both the contemporary arts and digital media fields of creative practice has been maintaining a strong awareness of other practitioners, current innovations, developments, trends and zeitgeists. The Blackaeonium archival system and the artworks that form the research project were created with these methods, using an iterative cycle of research, creation, experimentation, testing, and dissemination/exhibition – akin to the iterative cyclic model developed by Smith and Dean (Figure 0.20) in their publication Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts (Smith & Dean 2010, p. 20)

Figure 0.20 Iterative Cyclic Web of Practice-led Research and Research-led Practice, (Smith & Dean 2010, p. 20)

(image with permission from the authors)

(click to view larger image)

4. The method of “assemblage” which also includes the processes of selection, collection, recombination, juxtaposition, remix and reorganization of content to produce artworks. This method is something common to many contemporary artists’ practices. Here it has become a framework for viewing the archival collection as archival assemblage – a complex, rhizomatic structure that enables multiplicities of meaning and narrative through engaging with the creative content in the archive as both creator and audience.

5. The dissemination of works produced during the research project (the archival system and the artworks) through a process/method described as “tiering” (Dena 2007) whereby artworks are placed in the public domain through the use of various virtual and physical means – websites, social media applications, virtual and physical exhibitions – both curated and artist-led initiatives.

6. Discussion and discourse with peers – viewing each others’ artworks, discussing current topics related to contemporary art and variable media, engaging in group exhibitions based upon themes or issues, working collaboratively in creative projects and in the development of digital media products and curricula.

Two other complementary methodologies were employed in the research project: Agile software development methodology; and Archival methodology. The following section briefly outlines these methodologies and how they have been used.

Agile Software Development methodology (Beck et al. 2001) was followed as much as possible (for a single developer) within the broader framework of practice-based research, in the methods of coding and developing interfaces for the archival system prototypes – to facilitate rapid deployment of system modules whilst creating and documenting artworks.

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

(Beck et al. 2001)The system was developed using Agile methods because initially the “client” and the “developer” were one and the same, and these methods were most suitable for a creative media project, developing variable media artworks. Later when working with other artists, working in a more Agile way allowed for rapid redevelopment of interfaces and responsive change to the structure and content in the systems to suit the artist participant “client” needs.

The methods used here are similar to that of other forms of software development, but as time and resources were limited (I was a solo developer without a team of experts), this prevented creation of detailed specification documentation showing each change and development in the prototypes. Methods used were wire-framing, and sketching interfaces required for the system, creating sample files that tested certain modules of functionality before implementing them in the system itself, generating diagrams and tabulated data to show conceptual development of system structures, and printing pages from the system to use as testing checklists for each interface. A general specification document for the Blackaeonium archival system database structure was created and updated throughout the research (Appendix 2: Blackaeonium Archival System Specification Document), and the research project blog was used to document and reflect upon developments as they were happening. The blog was also used for the analysis and evaluation of archival documentation and creation of the artworks in the Blackaeonium archival system.

The different prototype versions of the Blackaeonium archival system that have been developed can be viewed online (except for Prototype 1 which has been removed and archived in the PhD research blog). The ACW archive is Prototype 2, the Blackaeonium and At Home archives are Prototype 3 (my own Blackaeonium archive as a site for experimentation, is also a testing ground for certain developments that are trialled before being implemented in other archival system iterations) and the Atemporal archive is becoming Prototype 4 as new developments continue to be added. Once Prototype 4 has reached a level of development ready for roll-out, Blackaeonium and At Home archives will be updated to the latest version.

Archival methodology was used throughout the research project for the documentation of creative content in the Blackaeonium archival system following the principals of Respect des fonds, and the physical and moral defence of records, “to ensure both the physical security and the intellectual integrity of the records as evidence”, as summarised in “Basic concepts and principles of archives and records management” (Pederson 2001). There is a rich history of archival practice in Australia, from significant archivists like Peter Scott who began working in the Australian Archives in the 1970s, to current practices taught to archives students in our universities such as Monash University and John Curtin University. Australia has many leading researchers in the field of archival science (which will be further discussed in Chapter 1). The archival methods employed in this research project were based upon my own experience as a student of archives and records at the University of Melbourne, and through my years of work at the University of Melbourne on diverse projects archiving records relating to medicine, science and technology.

Archival methods involve the selection and documentation of creative content in the Blackaeonium archival system. Documentation methods focused on accepted archival practice in establishing context for items in the archive, relationships between items, and the nature of items as authentic and reliable evidence and trace of the creative act/event.

The combination of methodologies used throughout the project will be discussed in Chapter 2, Chapter 3 and Chapter 4, which focus on the development of the experimental archival system prototype and the artworks that were created and documented throughout the research project. The documentation of methods is interwoven in these chapters because a practice-based research methodology was used throughout the project.

The system prototype and creative content have been evaluated from an artistic perspective, not an information system perspective. There are tensions that arise in the use of an experimental system where concepts such as user experience, usability and standards for systems development and metadata management may conflict with artistic selection and agency.

The artistic intent is to rupture and deconstruct the formal and standard elements that are expected from information systems as a means of questioning the relevance of these systems to the artist, and as a means of testing their validity to creative practice. If institutional and commercial systems and methods are not currently accessible or suitable (as they are not), then seeking other means may produce some useful outcomes.

Practice-based research allows for the research to embark on a journey in a way that Curt Cloninger describes as a “rigorously structured accident”. The research project becomes a framework for events and incidents.

Deleuze and Guattari propose a speculative/experimental practice of deterritorialization. You intend to head somewhere, but by definition you can't know where it will lead or how things will emerge at the end of your line. It is a kind of rigorously structured accident. Such speculative practices presume the possibility of something between intention and accident, a yet to have emerged space, an event of emergent becoming (to tap Whitehead). To tap Bergson, an actualization of the virtual. (Cloninger 2011)

The research also examines the tensions between artistic intent and archival intent – using practice-based research methods. The system cannot be wholly evaluated separately from the artworks it was created to document, and the research methods and processes used have infiltrated the creative practice, influencing the development of recombinant and new artworks.

Some of the tensions that were exposed through undertaking the research can be summarised here. These areas will be discussed further in Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, and in the conclusions drawn in the final section of the exegesis:

- The documentation process – how much documentation? To what granularity?

- The selection process: what to keep; and what not to keep?

- Defining the “artwork” in the context of the archival assemblage;

- The extent of preservation intervention - what is being kept and documented, what is being preserved?

- Requirements for stakeholders other than the artists/creators;

- Resistance: how can we address resistance to archiving by artists?

- Variable media and web technologies - how do web technologies impact upon creative practice in variable media arts?

top of page | homepage & table of contents | next section - chapter 1

Endnotes

[1] The word “remix” requires definition here because of the prevalence of popular culture music remix. Remix in digital media arts has also become a “hot” topic of discussion for academics in arts and humanities. This research will make reference to the significant work of artists and theorists such as Eduardo Navas (Navas 2011a), and Mark Amerika (Amerika 2011a, 2011b) amongst others. In the context of my statement – “the archival assemblage as slow remix”, remix refers to the creative practice of re-using or re-purposing existing content to create new work. It falls into the category of cultural practice that Navas describes as “a form of discourse”, “intertextuality” and “Regenerative Remix” (Navas 2011b). The archival assemblage, as it develops, shifts and morphs over time and space, is ever becoming a remix, slowly forming and reforming what Bill Seaman calls a “recombinant poetics” (Seaman 1999).

[2] Variable media art may be ephemeral digital, analogue, performed, installed and/or evental works. The preservation strategies discussed in this exegesis for variable media artworks are best defined by the Variable Media Network as follows:

"The variable media paradigm allows creators to choose from four strategies to tackle the obsolescence of a particular medium, such as the bulbs of Dan Flavin's fluorescent light installations.

Storage

The most conservative collecting strategy-the default strategy for most museums-is to store a work physically, whether that means mothballing dedicated equipment or archiving digital files on disk. Storing one of Flavin's fluorescent light installations simply means buying a supply of the out-of-production bulbs and putting them in a crate. The major disadvantage of storing obsolescent materials is that the work will expire once these ephemeral materials cease to function.

Emulation

To emulate a work is to devise a way of imitating the original look of the piece by completely different means. Emulating a Flavin fluorescent light installation would require custom-building fluorescent bulbs that produce the same light as and resemble the physical appearance of the original bulbs. Possible disadvantages of emulation include prohibitive expensive and inconsistency with the artist's intent. For example, Flavin deliberately chose to use ordinary off-the-shelf components rather than esoteric materials or techniques.

Migration

To migrate an work involves upgrading equipment and source material. The obsolete fluorescent bulbs of Flavin's light installation could be upgraded to fluorescent or halogen lights of comparable hue and brightness. The major disadvantage of migration is the original appearance of the work will probably change in its new medium. Even if state-of-the-art fixtures cast similar light to Flavin's originals, the actual fixtures are likely to look different.

Reinterpretation

The most radical preservation strategy is to reinterpret the work each time it is re-created. To reinterpret a Flavin light installation would mean to ask what contemporary medium would have the metaphoric value of fluorescent light in the 1960s. Reinterpretation is a dangerous technique when not warranted by the artist, but it may be the only way to re-create performance, installation, or networked art designed to vary with context."

(Variable Media Network 2006)

[3] excerpt from my PhD Blog - entry 29/02/2012 <http://multimedia.tafe.vu.edu.au/lcianci/mablog/members/blog/blogpopup1.cfm?blogID=810 >

A quote from the article by Rinehart:

"All preservation strategies include one or more of the above approaches, whether explicitly or implicitly. At first, the two most interesting approaches offered so far, coming from Rothenberg and Ippolito, would seem to be at odds - one proposing emulation, the other remaking. However, these views are readily reconciled when you consider that both actually propose re-creation of the original digital art work according to a set of instructions. The difference lay in the amount of automation or human touch applied to the process. Automation guarantees fidelity, efficiency, scalability and ultimately feasibility, but even Rothenberg admits that human touch and judgment will be required for emulation too. This is part of why human-readable metadata is required as part of the emulation package. Retrieving or re-presenting the digital art work then becomes a continuum of options facilitated by emulation and automation at one end and human intervention on the other. " (Rinehart 2000)

This article, and all the others I've read by Rinehart are very central to the issue for artists as well as the artworks. In particular, the section about human intervention, and who better to intervene than the artist him/herself? By documenting intent as Ippolito recommends (with the Variable Media Questionnaire), then interventions can be carried out on behalf of the artist if the artist is not available. In summary, the re-making or re-presentation of artworks enabled by contextual documentation, is the best method of preservation. Recombinant works that are documented in an archival assemblage, have these methods in-built, and as such may be the most future-proof option possible for an individual artist without institutional resources and mandates.

URL: http://switch.sjsu.edu/nextswitch/switch_engine/front/front.php?artc=233[4] Some of these email posts contain a three-part essay by Ippolito titled “why art should be free”

part 1 - http://lists.cofa.unsw.edu.au/pipermail/empyre/2002-April/msg00042.html

part 2 - http://lists.cofa.unsw.edu.au/pipermail/empyre/2002-April/msg00043.html

part 3 - http://lists.cofa.unsw.edu.au/pipermail/empyre/2002-April/msg00044.html

(Empyre 2002)[5] Examples of current remix in media arts include Mark Amerika’s “Remix the Book” (Amerika 2011a) - "Everything is a Remix", Kirby Ferguson (Ferguson 2011), “Remix Theory”, Eduardo Navas (Navas 2011a), “RiP: A Remix Manifesto", Brett Gaylor (Gaylor 2009)

[7] Blackaeonium has no particular reference to any technical aspect of the research, although it has serendipitously come to have an appropriate meaning to the project over time. The word “aeonium” (meaning ageless in Greek), and the combination of black with aeonium suggests something deep and timeless - atemporal perhaps. The aeonium looks like a flower, but is a succulent plant with leaves in a rosette formation. It's a very hardy plant that requires little water and doesn't wither in the hot sun. I am attracted to all the aspects of this plant, and have a substantial collection growing on my balcony. The black aeonium is something “more” than the ordinary green aeonium, and this reminds me of the scene in Peter Greenaway’s film “The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover” (Greenaway 1989), where the chef discusses how black foods are always more expensive – perhaps a reminder of mortality. There is a certain caché regarding things that are black. Also, black is all colours and no colour simultaneously (subtractive and additive colour).

Intuitively the name was selected as a domain name, and also as a way of avoiding the use of some clever acronym for a software system as so many developers seem to do. The atemporal nature of the name is now a fortunate happenstance, and a good name for the archival system because of all these meanings.[8] It is important to note that Lyndal Jones was also my PhD supervisor from 2005-2012 although, the At Home archival project became a formal arrangement between myself as archival consultant and developer and Jones as the artist/client. She was invited to participate in the research project because her creative practice is significant, the scale of her projects is substantial, and she is an important female Australian artist who has created some key performance and installation artworks from the 1970s to the present day. Furthermore, she had the necessary patience to participate in the laborious process of digitisation and archiving of the At Home series, and she was able to provide an exhibition context enabling others to publicly engage with the project.

[9] The name “Atemporal” comes from the keynote speech by Bruce Sterling at Transmediale 10, Berlin, Feb. 6, 2010 titled “Atemporality for the Creative Artist” (Sterling 2010), which I found to be resonant as a concept that also relates to Frank Upward’s definition of the Continuum in “Continuum Mechanics and Memory Banks: (1) Multi-polarity” (Upward 2005).

[10] See the Indigo Aeonium (Cianci 2011) portal homepage at <http://indigo.blackaeonium.net> for updates of and links to guest remixes in the Blackaeonium Archive.

[11] The GPG was a contemporary art space active in the 1970s and ‘80s. The collection of records and artefacts of the GPG is kept at the University of Melbourne Archives, and after the closure of the gallery, these records were stored in the archives, but were completely undocumented at that time. My task was to piece together a history of the gallery and put the slide collection into context. I listed events, participating artists and speakers, and documented the slides that were evidence of these events. It was this first meshing of art, archives and digital media that started me on my current research path.

[12] After the archives course, I worked for several years as an archivist in an organisation at The University of Melbourne that undertook heritage projects relating to medicine, technology and science archives – The Australian Science Archives Project (ASAP)(Australian Science Archives Project 1999). One of the main concerns at ASAP was provision of access to the objects in different ways through print publications, websites, interpretive displays and exhibitions - not just preservation of the objects we were documenting. The multiple formats (both analogue and digital) that ASAP used to provide access to archival objects allowed unprecedented access for users primarily because much of the digital material became accessible on the Internet, or in public spaces, and we were able to start building links between collections via websites, databases, and other formats for archival finding aids (eScholarship Research Centre 1994). Through exposure to this work, my own artwork became increasingly digital in format, and I found that tools I was using in my archival work were useful in my art practice.

[13] To date, I possess 4 external hard disks, 3 computers and hundreds of CD and DVD disks – all of which contain at least 5 - 6 terabytes of data that have accumulated over the last 17 years. From discussions with peers and colleagues, it is apparent that this is not unusual for a media artist – especially one working with rich media such as video and Flash content.

[14] I have chosen to use the term “Practice-based” as opposed to “Practice-led”, based upon the definitions of these two research methodologies by Candy and Edmonds from the Creativity and Cognition Studios at The University of Technology. They describe the difference essentially as this: “If a creative artefact is the basis of the contribution to knowledge, the research is practice-based. If the research leads primarily to new understandings about practice, it is practice-led.” (Candy 2006)

[15] Creative artefacts are the basis of the contribution to knowledge in this research, although one could make the argument that new understandings about practice may also be elucidated from the processes and methods developed to undertake the project – thus practice-led to some extent. Though, ultimately, all areas of theory and practice examined through the research have been synthesized into the project outcomes – creative artefacts.

[16] Metacontent as a term (usually written “meta content”) is generally associated with HTML or XML “meta content” tag content descriptors. Metacontent has been appropriated here (and written as one word) to distance it from the realm of markup language terminology because it is a more suitable word than “metadata” for the purposes of this research. Metadata is a popular term that archivists and web developers alike are familiar with. Essentially it means “data about data”. This research into both archival systems and new media art has located many references to metadata, but it is preferable to use the term metacontent because it relates more specifically to the idea of descriptive content, not of objects and data, which are words from the Information Technology world, not that of artists and creative practitioners. Metacontent is then defined as “content about content” – and could potentially be anything analogue or digital. My understanding of "metacontent" comes from a concept based upon this description from the Educational Technologies Blog,

The term metadata is an ambiguous term which is used for two fundamentally different concepts (types). Although the expression "data about data" is often used, it does not apply to both in the same way. Structural metadata, the design and specification of data structures, cannot be about data, because at design time the application contains no data. In this case the correct description would be "data about the containers of data". Descriptive metadata, on the other hand, is about individual instances of application data, the data content. In this case, a useful description (resulting in a disambiguating neologism) would be "data about data contents" or "content about content" thus metacontent.

(Educational Technologies Blog 2011).

top of page | homepage & table of contents | next section - chapter 1

this page produced by lisa cianci on her website www.blackaeonium.net

comments and queries to lisa's email address on scr.im (for humans only)

created 01/12/2011

last modified 30/07/2012